Josh Kline

Universal Early Retirement (Spots #1 & #2) (2016)

OCTOBER 11th–28th, 2018

Bangkok Citycity Gallery

Fast forward ten or twenty years from our present– half a generation. Another American presidential election is scheduled for Fall 2031. Baggy skater pants are back in style in the suburbs. And increasingly intelligent software has turned out the lights on a hundred million jobs. Most of the middle class will never work again. Considered too old, too expensive, too obsolete, and too set in their ways for the faster–paced time in which they find themselves, the majority of people in middle age—born in the 1970s and ‘80s–have no future prospects for professional employment. Lawyer, accountant, banker, administrator, manager, secretary—these now expendable careers have been starved to near–death, following professions like taxi driver, truck driver, train conductor, and factory worker into automated oblivion. What is to be done with the hundreds of millions of people who will never “earn” another paycheck? What is to be done with you?

And what will you do? Will you prowl the streets scavenging pennies and nickels from discarded plastic and glass? Will you Airbnb your body out to strangers in order to make rent? Your mind has left the real economy, but your body still needs to eat food and spend its days somewhere. In a sharing economy, people subscribe instead of owning, so Suburbia’s growing homeless population can’t sleep in their cars anymore.

Income inequality scales exponentially. And unemployment escalates up the asymptote along with it. The money version of Moore’s Law. 21st Century economic crises come equipped standard with a jobless recovery and more effective, efficient automation. Every recession from here on out will close with an ever more brutally competitive round of musical chairs around a diminishing number of lower and lower–paid employment possibilities. If you’re left standing at the end without a job, it’s your own fault, right?

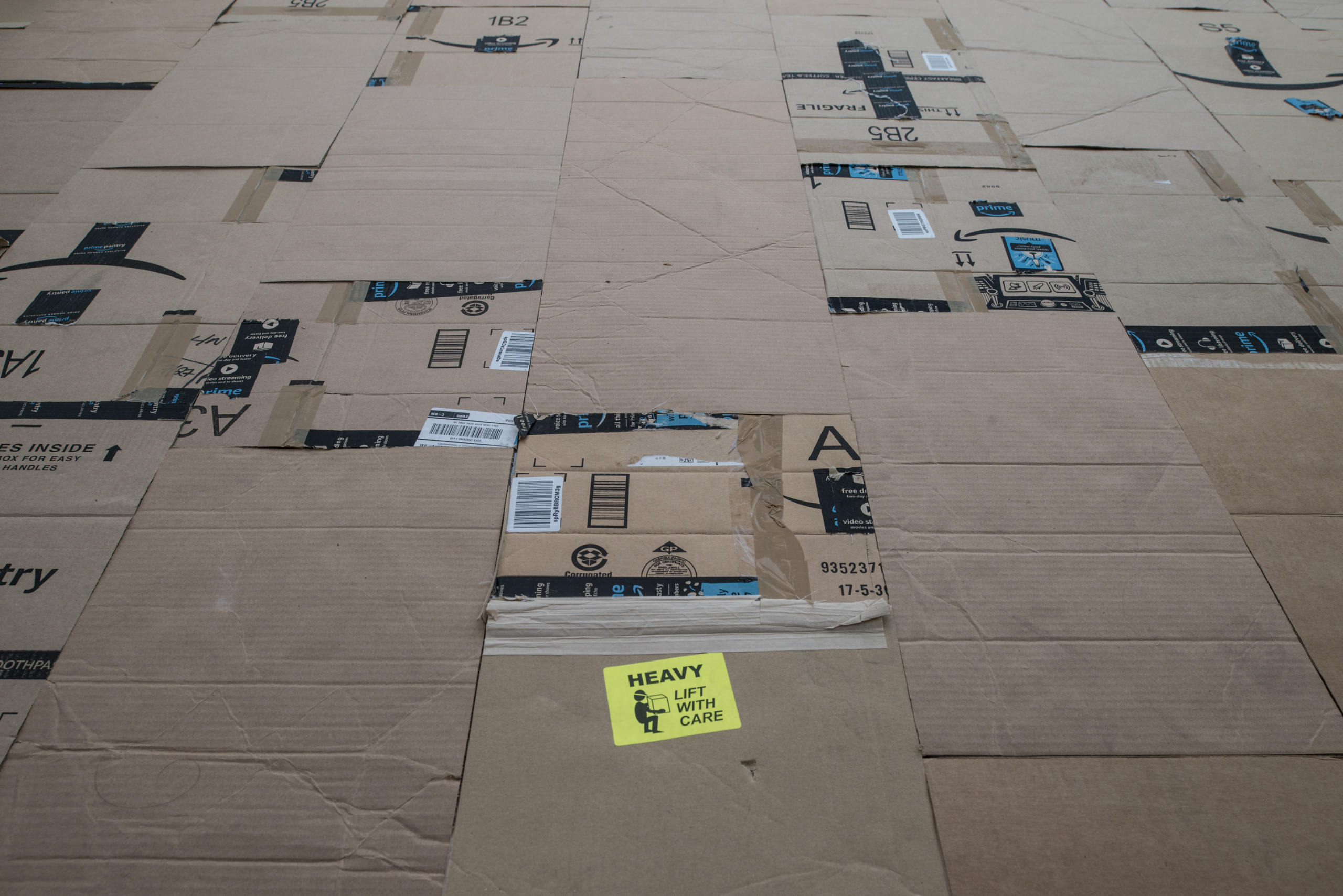

In its heyday, middle–class status in the “developed” world was a kind of sanctified protection racket. In exchange for giving over most of your waking life to mind/body drudgery, a reasonably–salaried job offered shelter from the market’s harsher elements. As the fairytales about a trickle–down future for you and your great–grandchildren expire and evaporate— instead of financial security, disposable income, material comfort, and leisure, you’re left holding a go–bag filled with desperation, debt, and fear. Plush carpeting replaced with dirty discarded cardboard.

Among the “disruptors” in Silicon Valley’s upper echelons, the nameless, faceless millions whose livelihoods are being fast–tracked for the abattoir are often seen as necessary casualties of progress. Unavoidable victims. On the other side of automation’s promise, the public is told that there will be new jobs for the next generation. That a whole new ecosystem of sustainable employment will bubble up around the new sharing economy. Prior to World War I—before the mass adoption of the horseless carriage—millions of horses toiled in the shit–filled streets of the world’s great cities and on the bloody battlefields of the West. After the war—in less than a generation, they were replaced by internal combustion engines. Where did all the horses go?